What a Fish Knows: An interview with Dr. Jonathan Balcombe

People love animals, so it’s no surprise that books about animals are perennial bestsellers. Ethologist Dr. Jonathan Balcombe has published five books on animal behavior. His latest, What a Fish Knows: The Inner Lives of Our Underwater Cousins, looks at animals few of us know much about. A New York Times Bestseller, What a Fish Knows, takes us “under the sea, through streams and estuaries, and to the other side of the aquarium glass to reveal the surprising capabilities of fishes.” We recently sat down with Dr. Balcombe to ask him a few questions about the book.

Table of Contents

- Thanks so much for taking the time to answer these questions and congrats on the success of the book! I grew up keeping fishes and always found them to be fascinating. Yet they tend to be rather difficult for us to relate to. What inspired you to write this book?

- What a Fish Knows was so well researched and illuminates many lesser known facts about fishes. What did you discover in your research that intrigued you the most?

- For some time what many believed what was a uniquely human skill was our use of tools. Increasingly we’re learning non-human animals use tools as well. As you outlined in your chapter “Tools, Plans, and Monkey Minds,” fishes are among them. Can you talk a little about some of the ways fishes have been discovered using tools?

- It’s pretty clear that fishes are different from us in many ways. How are they like us?

- You close What a Fish Knows with a chapter on the issues facing fishes in the age of humans. Of those, what do you see as the most pressing?

- Do you have any advice on how we all can help make a difference for fishes?

Thanks so much for taking the time to answer these questions and congrats on the success of the book! I grew up keeping fishes and always found them to be fascinating. Yet they tend to be rather difficult for us to relate to. What inspired you to write this book?

JB: Indeed, humans have a difficult time relating to fishes, and I think it’s mainly because they have evolved in a different realm. It’s only in the past 75 years that advances in underwater exploration and filming technology have advanced to the point that we can closely examine fishes’ lives in the wild.

I was inspired to write What a Fish Knows when I became aware of fascinating scientific discoveries about fishes that revealed rich, complex lives, and I realized how very little of this information was reaching the public consciousness. The primary aim of this book is to make this stuff accessible to non-scientists, in the hope that we will adopt a more empathic relationship to fishes.

What a Fish Knows was so well researched and illuminates many lesser known facts about fishes. What did you discover in your research that intrigued you the most?

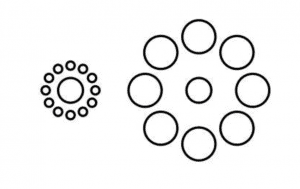

JB: It’s hard to choose just one thing from hundreds of discoveries, but let me pick optical illusions. Fishes can be trained to select between two or more choices, by pushing a button with their nose, squirting water at a target, etc. This method has been used to show that fishes fall for the same optical illusions that we do. For example, when trained by food rewards to select the larger of two circles, then presented with the Ebbinghaus optical illusion (see below), fishes prefer one of an identical pair of circles that appears larger because of its placement among smaller circles (i.e., the central circle on the left in the figure).

For some time what many believed what was a uniquely human skill was our use of tools. Increasingly we’re learning non-human animals use tools as well. As you outlined in your chapter “Tools, Plans, and Monkey Minds,” fishes are among them. Can you talk a little about some of the ways fishes have been discovered using tools?

JB: Lacking grasping limbs, fishes have limited options for tool-use, but that hasn’t stopped them. Many fishes use jets of water as a tool, either underwater or above the surface. Certain members of the wrasse family have been seen (and in at least one case, filmed) blowing water at the sand to uncover edible mollusks, then carrying the shellfish to a rock which is then used as an anvil against which to smash the bivalve with a series of well-timed head flicks and releases.

Archerfishes use water more directly as a hunting tool. They catch insects by squirting jets of water up to 10 feet through the air. With lots of practice, they develop the skill to pick off flying insects with remarkable accuracy. They use different techniques according to the situation, and they hone their skills by watching others.

It’s pretty clear that fishes are different from us in many ways. How are they like us?

JB: Falling for an optical illusion shows that a fish can have beliefs; that’s pretty human-like. The communication between groupers and moray eels is also eerily familiar to how we may use gestures to get the attention of someone else. Groupers perform head shakes or body shimmies to signal to moray eels that they want to team up for a cooperative hunting outing. Groupers will perform headstands, using their bodies to point to a prey fish hiding in the reef, and hoping that nearby moray will come to investigate. If the fish gets flushed out by the eel, the grouper is more likely to catch it. These referential signals are regarded by scientists as high-level cognitive feats.

You close What a Fish Knows with a chapter on the issues facing fishes in the age of humans. Of those, what do you see as the most pressing?

JB: There are several crises threatening fishes and their habitats. The most serious is nothing new: commercial and recreational fishing. Hundreds of billions, possibly trillions, of fishes are killed each year for human consumption, or for sport. Then there are the problems of ocean warming and acidification, leading to the deterioration of coral reefs, which are home to the highest diversity of marine creatures. An insidious problem gaining attention now is the presence of plastic garbage. A 2014 study by World Animal Protection estimates that we leave 640 thousand tons of discarded fishing gear in the oceans each year. Also, the oceans are being inundated with micro-plastic beads, of which quadrillions can be found floating around in oceans and seas; these tiny balls—byproducts of plastics manufacture which inevitably flow downstream—are ingested by larval fishes, causing their stomachs to rupture.

Do you have any advice on how we all can help make a difference for fishes?

JB: We’ve lost half of all marine life over the past half-century, according to a joint study released in 2015 by the World Wildlife Fund and the Zoological Society of London. It doesn’t have to continue. Few of us depend on eating fish for our survival, and the problems of climate change and ocean garbage are addressable if we take responsibility for changing our ways. We urgently need new laws and policies designed to forcefully protect sea habitats and their denizens. Individuals can also take the immediate step of reducing or eliminating their consumption of fishes, which cuts financial support for destructive commercial practices.

Thank you so much for your time and for helping raise awareness of these misunderstood beings!

What a Fish Knows by Dr. Jonathan Balcombe is available on Amazon.com and major booksellers across the U.S.

If this article was helpful to you, make sure to read our related article about shark finning and its impact on our planet’s oceans. Anything we can do to increase awareness helps to decrease the suffering of sea creatures is impactful and important.

Leave a Comment